Property-Driven Training

Motivation

We finished the last chapter with a conjecture concerning

diminishing robustness verification success with increasing values of

The last exercise of the previous chapter gave us a property specification

for robustness of “Fashion MNIST” models. We propose now to look into the statistics of verifying one of such models on 500 examples from the data set. To obtain quicker verification times, let us use a Fashion MNIST model with one input layer of

| 82.6 % (413/500) | 29.8 % (149/500) | 3.8 % (19/500) | 0 % (0/500) |

As we see in the table, verifiability of the property deteriorates quickly with growing

Can we re-train the neural network to be more robust within a desirable

Let us look closer into this.

Robustness Training

Data Augmentation

Suppose we are given a data set

However, this method maybe problematic for verification purposes.

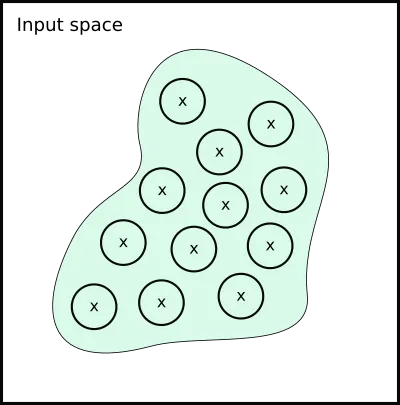

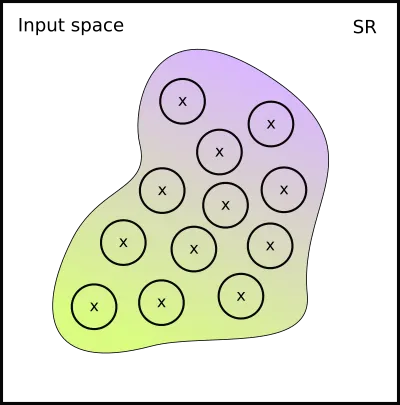

Let us have a look at its effect, pictorially. Suppose this is the manifold that corresponds to

Remember that we sampled our new data from these

We have a problem, because some of the data points we sampled from the suddenly have wrong labels!

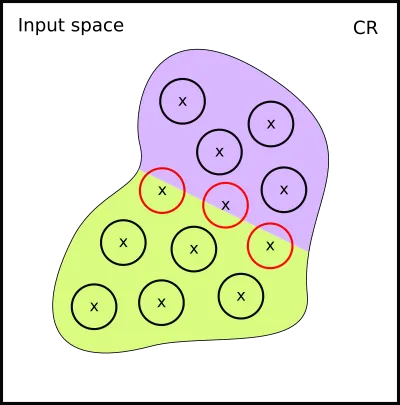

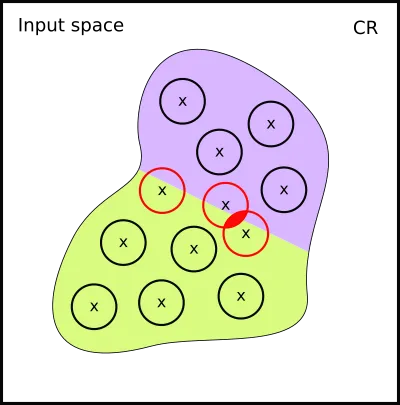

Actually, it maybe even worse. Depending how our data lies on the manifold, we may have even generated inconistent labelling. Here is the example when this happens:

It seems data augmentation is not general enough for Vehicle, and only works correctly if strong assumptions about the underlying manifold are taken.

Adversarial Training

It would be nice to somehow reflect the fact of proximity to the decision boundary in our training! The closer the point is to the decision boundary, the less certain the neural network should be about its class:

However, using data labels as a method is unfit for the task. We cannot achieve the effect we are looking for with data augmentation. We have to modify our training algorithm instead Goodfellow, I. J., Shlens, J., & Szegedy, C. (2015). Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. In Y. Bengio & Y. LeCun (Eds.), 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, May 7-9, 2015, Conference Track Proceedings. .

Loss Function

Given a data set

computes a penalty proportional to the difference between the output of

The reader will find an excellent exposition of adversarial training in the tutorial by Kolter, Z., & Madry, A. (2018). Adversarial Robustness - Theory and Practice. In NeurIPS 2018 tutorial. .

Example: Cross-Entropy Loss

Given a function

where

Adversarial Training for Robustness

Gradient descent minimises loss

For adversarial training, we instead minimise the loss with respect to the worst-case perturbation of each sample in

The inner maximisation is done by projected gradient descent (PGD), that “projects” the gradient of

Adversarial Training and Verification

Adversarial training is almost the right solution!

Its main limitation turns out to be the logical property it optimises for.

Recall that we may encode an arbitrary property in Vehicle. However, as we discovered in Casadio, M., Komendantskaya, E., Daggitt, M. L., Kokke, W., Katz, G., Amir, G., & Refaeli, I. (2022). Neural Network Robustness as a Verification Property: A Principled Case Study. In S. Shoham & Y. Vizel (Eds.), Computer Aided Verification - 34th International Conference, CAV 2022, Haifa, Israel, August 7-10, 2022, Proceedings, Part I (Vol. 13371, pp. 219–231). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13185-1\_11

, the projected gradient descent can only optimise for one concrete property.

Recall the property of

Logical Loss Functions

Is there any way to generate neural network optimisers for any given logical property?

The main idea is that we would like to co-opt the same gradient-descent algorithm that is used to train the network to fit the data to also train the network to obey the specification.

Logical Loss Function: Simple Example

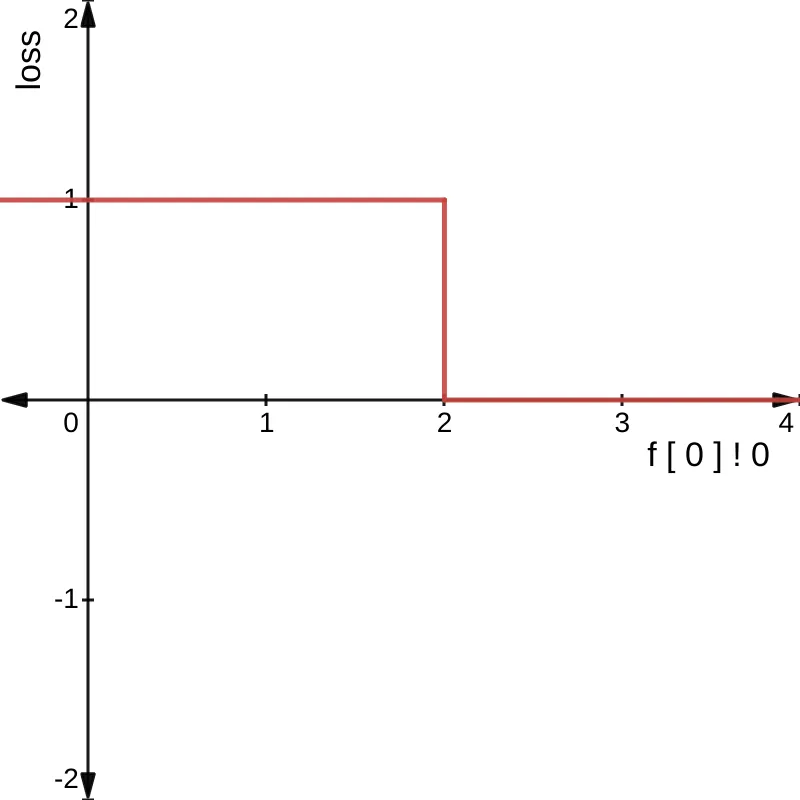

Consider the very simple example specification:

@network

f : Tensor Real [1] -> Tensor Real [1]

@property

greaterThan2 : Bool

greaterThan2 = f [ 0 ] ! 0 > 2

This statement is either true or false, as shown in the left graph below:

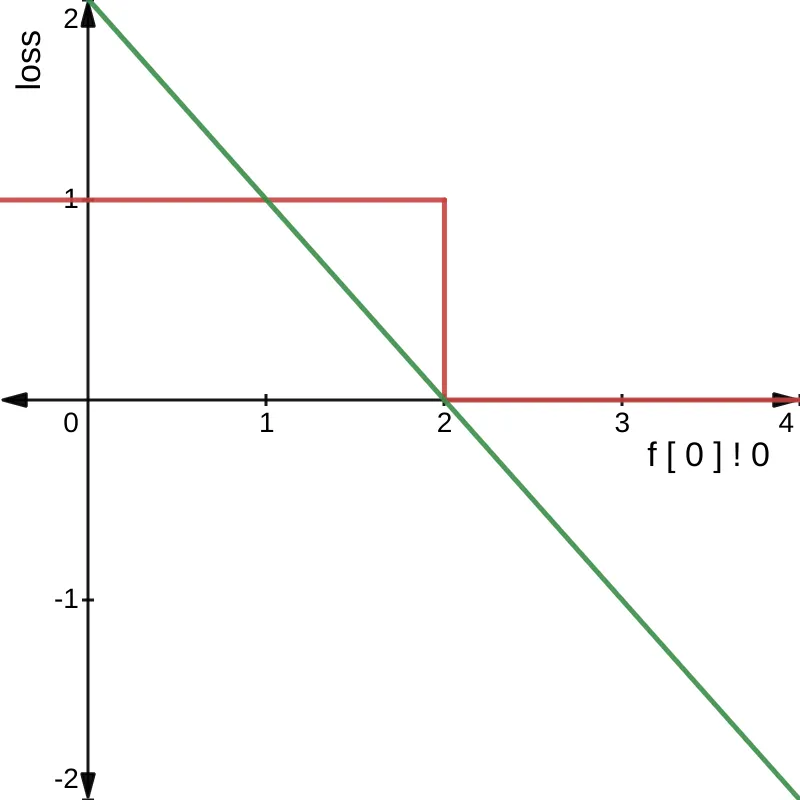

However, what if instead, we converted all Bool values to Real, where a value greater than

0 indicated false and a value less than 0 indicated true?

We could then rewrite the specification as:

greaterThan2 : Real

greaterThan2 = f [ 0 ] ! 0 - 2

If we then replot the graph we get the following:

Now we have a useful gradient, as successfully minimising f [ 0 ] ! 0 - 2 will result in the property greaterThan2 becoming true.

This is the essence of logical loss functions: convert all booleans and operations over booleans into equivalent numeric operations that are differentiable and whose gradient’s point in the right direction.

Differentiable Logics

Traditionally, translations from a given logical syntax to a loss function are known as “differentiable logics”, or DLs. One of the first attempts to translate propositional logic specifications to loss functions was given in Xu, J., Zhang, Z., Friedman, T., Liang, Y., & den Broeck, G. V. (2018). A Semantic Loss Function for Deep Learning with Symbolic Knowledge. In J. G. Dy & A. Krause (Eds.), Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2018, Stockholmsmässan, Stockholm, Sweden, July 10-15, 2018 (Vol. 80, pp. 5498–5507). PMLR. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/xu18h.html and was generalised to a fragment of first-order logic in Fischer, M., Balunovic, M., Drachsler-Cohen, D., Gehr, T., Zhang, C., & Vechev, M. T. (2019). DL2: Training and Querying Neural Networks with Logic. In K. Chaudhuri & R. Salakhutdinov (Eds.), Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2019, 9-15 June 2019, Long Beach, California, USA (Vol. 97, pp. 1931–1941). PMLR. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v97/fischer19a.html . Later, this work was complemented by giving a fuzzy interpretation to DL by van Krieken, E., Acar, E., & van Harmelen, F. (2022). Analyzing Differentiable Fuzzy Logic Operators. Artif. Intell., 302, 103602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2021.103602 and Slusarz, N., Komendantskaya, E., Daggitt, M. L., Stewart, R. J., & Stark, K. (2023). Logic of Differentiable Logics: Towards a Uniform Semantics of DL. In R. Piskac & A. Voronkov (Eds.), LPAR 2023: Proceedings of 24th International Conference on Logic for Programming, Artificial Intelligence and Reasoning, Manizales, Colombia, 4-9th June 2023 (Vol. 94, pp. 473–493). EasyChair. https://doi.org/10.29007/c1nt proposed generalisation for the syntax and semantics of DL, with a view of encoding all previously presented DLs in one formal system, and comparing their theoretical properties.

Vehicle has several different differentiable logics from the literature available, but will not go into detail about how they work here.

Instead, we explain the main idea by means of an example. Let us define a very simple differentiable logic on a toy language

One possible DL (called Product DL in van Krieken, E., Acar, E., & van Harmelen, F. (2022). Analyzing Differentiable Fuzzy Logic Operators. Artif. Intell., 302, 103602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2021.103602 ) for it can be defined as:

An example of this translation is:

Logical Loss Functions in Vehicle

We now have all the necessary building blocks to define Vehicle approach to property-driven training. We use the formula:

In Vehicle, given a property

where

is a hyper-shape that corresponds to the pre-condition and is obtained by DL-translation of the post-condition .

Let us see how this works for the following definition of robustness:

The definition of the optimisation problem above instantiates by taking:

given by the -cube around and - given any DL translation

, the loss function

Coding Example: generating a logical loss function in Python

The Python bindings ship backend-specific helpers in vehicle_lang.loss.tensorflow

and vehicle_lang.loss.pytorch. They both expose a single entry point

load_specification(path, ...) which compiles your .vcl file to a dictionary of

callable Python loss functions. The returned dictionary keys are the names of

@property declarations in your spec.

Below is a minimal PyTorch example that mirrors the tests in vehicle-python/tests:

import torch

from vehicle_lang.typing import DifferentiableLogic

from vehicle_lang.loss.pytorch import load_specification

# Compile the Vehicle spec to PyTorch loss functions

spec = load_specification(

"test_trainable.vcl", # any Vehicle spec path

logic=DifferentiableLogic.Vehicle,

)

constraint_loss = spec["output_bounded"] # name of a @property in the spec

train_x = torch.tensor([0.0, 0.5, 1.0], dtype=torch.float32).unsqueeze(1)

train_y = torch.tensor([0.0, 1.0, 2.0], dtype=torch.float32)

model = torch.nn.Sequential(

torch.nn.Linear(1, 8), torch.nn.ReLU(), torch.nn.Linear(8, 1)

)

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=1e-2)

for step in range(50):

optimizer.zero_grad()

# Task loss (e.g., MSE to a target function)

preds = model(train_x).squeeze(1)

task_loss = torch.mean((preds - train_y) ** 2)

# Constraint loss produced by Vehicle; signature matches the Vehicle property

constraint_loss_value = constraint_loss(model)

loss = 0.5 * task_loss + 0.5 * constraint_loss_value

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

Switching to TensorFlow changes only the backend import and model definition; the

property call still follows the spec’s argument list (typically a single

network callable for many specs):

import tensorflow as tf

from vehicle_lang.typing import DifferentiableLogic

from vehicle_lang.loss.tensorflow import load_specification

spec = load_specification("test_trainable.vcl", logic=DifferentiableLogic.Vehicle)

constraint_loss = spec["output_bounded"]

train_x = tf.constant([[0.0], [0.5], [1.0]], dtype=tf.float32)

train_y = tf.constant([0.0, 1.0, 2.0], dtype=tf.float32)

model = tf.keras.Sequential([

tf.keras.layers.Input(shape=(1,)),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(8, activation="relu"),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(1),

])

optimizer = tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=1e-2)

for step in range(50):

with tf.GradientTape() as tape:

preds = tf.squeeze(model(train_x), axis=1)

task_loss = tf.reduce_mean(tf.square(preds - train_y))

constraint_loss_value = constraint_loss(model)

loss = 0.5 * task_loss + 0.5 * constraint_loss_value

grads = tape.gradient(loss, model.trainable_variables)

optimizer.apply_gradients(zip(grads, model.trainable_variables))

Optional parameters such as logicand samplers are

available on load_specification; see the Python API docs for defaults and examples. To customise

how Vehicle searches adversarial points, you can supply your own sampler (cf. the default FGSM-based

samplers in the source tree) when you have domain-specific needs.